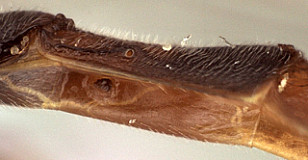

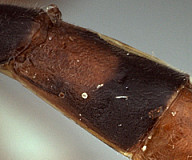

Clypeus broad, with surface usually coarsely punctate to transversely rugose; ventral margin usually evenly convex, more rarely broadly truncate or nearly so medially and convex laterally, the margin always blunt; epistomal sulcus weak to distinct, usually broad and shallow, defined largely by angulation of clypeus; clypeus in profile varying from weakly protruding, nearly flat to strongly protruding. Inner eye margins parallel. Malar space often absent (Fig. 3), less commonly short but present, at most 0.5 times basal width of mandible; malar sulcus absent. Mandible (Fig. 3) tapering very gradually towards apex; dorsal tooth varying from nearly equal in size to distinctly shorter than ventral tooth; ventral margin distinctly carinate. Maxillary palp usually shorter than height of head, more rarely as long as height of head; antenna often longer than body, about equal in length to body or even slightly shorter in some species. Ocelli small, diameter of lateral ocellus less than distance from lateral ocellus to eye. Hypostomal carina meeting occipital carina above base of mandible, with distance of junction from mandible varying among species; occipital carina complete dorsally. Epomia present. Epicnemial carina usually (90%) reaching anterior margin of mesopleuron. Notaulus present as a very distinct impression on anterior declivity, this part sometimes weakly sculptured, becoming more faint on disk and varying in extent on disk among species from absent or nearly so to broad, shallow, and converging in broad median depression posteriorly. Groove between propodeum and metapleuron absent to very weakly indicated, not u-shaped as in pionines; pleural carina present, often well-developed and complete, less commonly weak to absent or nearly so posteriorly; median longitudinal carinae varying among species: present only as low ridges posteriorly that are often lost among surrounding sculpture in some species, distinct posteriorly and partially effaced only anteriorly in other species, less commonly complete to anterior margin; forming flask-shaped median region, broad posteriorly and usually narrowly separated anteriorly; lateral longitudinal carina incomplete, usually extending from posterior margin to spiracle or nearly so, sometimes present only as short spurs off posterior margin; transverse carinae absent, though petiolar area sometimes nearly complete. Legs with apical margin of mid tibia usually only weakly expanded into a tooth, not similar to that of fore leg; apical comb on posterior side of hind tibia weakly developed to absent; posterior hind tibial spur about 0.3 times length of hind basitarsus, not particularly long; tarsal claws large, not pectinate, claws on hind leg sometimes asymmetrical, with one larger than the other; fifth tarsomere of hing leg often unusually elongate (relative to fourth), somewhat flattened, and curved (Fig. 1). Fore wing areolet present; stigma moderately broad, less commonly narrower as in Fig. 2, Rs+2r arising near basal 0.3-0.4. Hind wing with first abscissa of CU1 equal to or slightly shorter than 1cu-a. T1 long, slender (Figs 1, 2), parallel-sided or nearly so from base to spiracles, then broadening slightly towards apex; straight to weakly curved in profile; dorsal carinae usually absent or indistinct, sometimes sharp basad spiracles; basal depression at dorsal tendon attachment absent; dorsal-lateral carina often complete between spiracle and apex of T1; glymma absent. S1 extending at least to level of spiracle and rarely up to 0.75 times length of T1. T2 thyridium apparently absent (Fig 5), T2 sometimes with well-developed carina between spiracle and anterior margin as in Ctenopelmatini (Figs. 4, 5); laterotergites of T2 and T3 separated by creases from median tergite. Ovipositor and sheath (Figs 1, 2, 6) short; ovipositor with broad, dorsal, subapical notch. The species as a whole are generally long and slender.

The above description is modified from Townes (1970), and based in part on numerous specimens in the Texas A&M University collection.