Westwoodia ruficeps Brullé, 1846: 127-128.

Westwoodia ruficeps: Dalla Torre 1901: 310 (catalog); Roman 1912: 240-241, 292-293 (identity); Morley 1913: 101-102, 135-136 (redescription, figure, new distribution records); Viereck 1914: 152 (as type species of Westwoodia); Roman 1915: 3-5 (diagnosis, key, first description of male; new distribution records); Viereck 1921: 144 (type species listed); Townes et al. 1961: 213, 447 (catalog; key to genera); Townes 1970: 56-58 (redescription of genus; key to genera of Westwoodiini); Casolari and Casolari Moreno 1980: 59 (specimens in Spinola collection); Gauld 1984: 226-227, 233-234 (figures of species, redescription of genus, key to genera); Gupta 1987: 356 (catalog); Yu and Horstmann 1997: 456 (catalog).

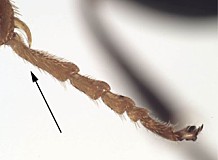

Westwoodia ruficeps was described from a single female specimen from Van Dieman’s Land (= Tasmania), “Collect. de M. Serville” (Brullé 1846). Many of the Brullé types from this work are in the Paris Museum, but it is also possible that Brullé returned the specimen to Audinet-Serville just before the Serville Collection was sold to Spinola in 1847. The Brullé Collection in the Paris Museum does not contain any specimens of Westwoodia, and Townes et al. (1961) stated that the type was lost. The Spinola Collection, however, contains two specimens of Westwoodia and although there is no locality label, they match in every respect material from the type locality. It is thus possible that one of these specimens is the holotype, but there is no way to be certain, especially since the Westwoodia specimens in the Spinola Collection apparently were obtained from Deyrolle rather than directly from Audinet-Serville (Casolari and Casolari Moreno 1980). Because populations from Tasmania are distinct in at least some respects from mainland populations, and since repeated attempts have failed to provide any evidence that the holotype still exists, we have designated a specimen from Hobart as neotype. The neotype was not selected from material in the Spinola collection because the two specimens examined are in poor condition.

Westwoodia ruficeps is the type species of the genus Westwoodia Brullé, 1846. Until recently (Gauld 1984), this was the only described species of Westwoodia.